Pubic hair, nudism and the censor: the story of the photographic battle to depict the naked body

Annebella Pollen, University of Brighton

I look at nude bodies all the time in my work. Art history is full of them – painted, sculpted and photographed – and they fill the walls of galleries and museums. I stand before them, projected on screens, as I lecture on the subject. Earlier in my career, I posed on the other side of the artist’s easel, as a life model, where I looked at artists looking at me. This dual perspective has given me a privileged position, as both subject and surveyor of the nude.

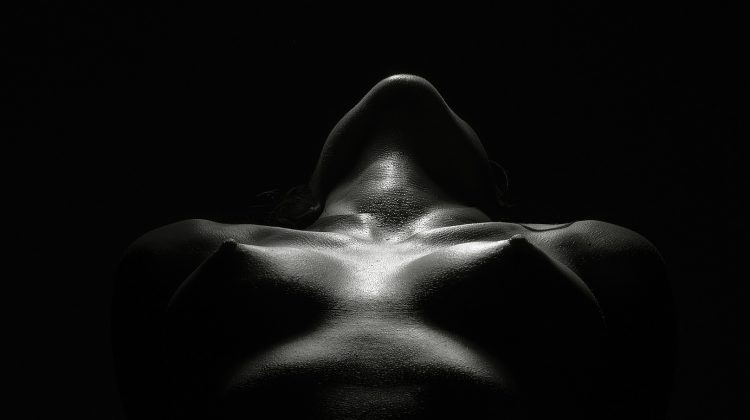

Contemporary artists might critique the nude’s traditions and ideals, but the naked body is still the ground on which debates play out. Nudes in art can now take a range of forms and styles but one key aspect prevails in art galleries: they are most likely to be of women and created by men.

Feminist activists the Guerilla Girls, who style themselves as the conscience of the art world, have kept a running count of exhibited works by female artists (around 4%) compared to the number of nudes that are female (around 76%) in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art for more than 30 years. The disparities remain stark.

The naked body and its visual depiction has always attracted attention and generated heated debate. What and who should be seen and shown, by whom and where, form the basis of the social and moral codes that shape behaviour and belief.

Today, the display of nudity remains contentious, particularly in the context of social media. This is both in relation to photographs of “real nude adults”, as Facebook describes them, and in relation to “artistic or creative” depictions of nudity, which are wholly banned by Instagram and its parent company.

While Facebook officially states that it permits nudity in images of paintings and sculptures, there have been famous recent cases where photographs of celebrated artworks, including the 25,000-year-old figurine, the Venus of Willendorf, and 17th century paintings by Peter Paul Rubens have been taken down and described as “pornographic”. To circumnavigate the censor, some museums have even recently opened accounts on OnlyFans, a controversial social media platform most often associated with the promotion and sale of material intended to sexually arouse, rather than the viewing of fine art.

How did we get here? In my new book, Nudism in a Cold Climate, I’ve been examining earlier attitudes to nude bodies, and their photographic depiction, especially in relation to legal restrictions around the representation of nudists (also known as naturists), and the depiction of nudes in photographs produced as art in mid 20th-century Britain. The historic parallels are striking.

Facebook, for example, currently does not permit the depiction of “visible genitalia”, with limited exceptions around birth and health contexts, and even in these cases, it requires photoshopping for nude close-ups. A century ago, photographic “retouching”, as it was called, was also required for male and female genitals to meet the requirements of obscenity law.

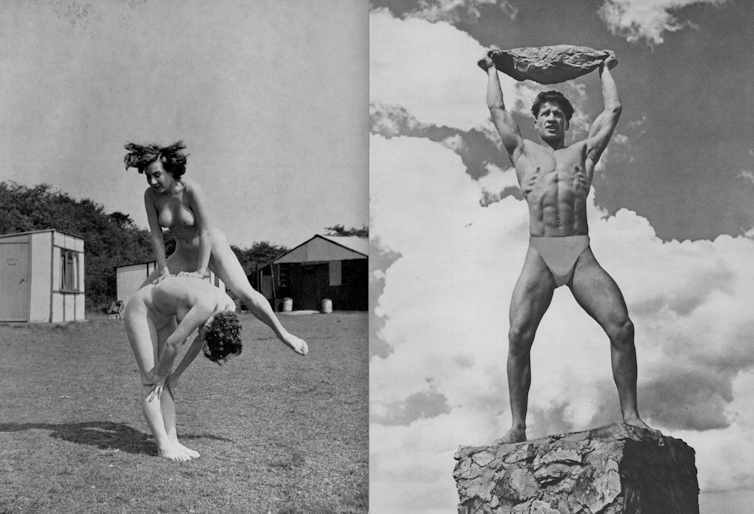

What this meant, in practice, was that the emerging nudist movement in Britain, formally founded in the 1920s but achieving popularity from the 1930s, could only depict nude bodies in their publications by photographing members and models in strategic poses that concealed sex organs and pubic hair. Where this was not possible, they needed to manipulate photographic negatives to blur genitals out, visually smooth them over, or even paint on underpants.

For a movement founded on liberation from convention and bodily visibility, this was a core contradiction, and the resulting photographs created a sense of forbidden fruit. This was exactly the message that nudists wished to avoid.

Nude for health

Early nudists insisted that going nude, outdoors, in groups, was good for physical and mental health. They also wanted a clear moral distinction to be made between nude bodies and sexual desire. They argued, in the 1930s, in the pages of their magazine, Sun Bathing Review, that “honest photography would induce mental honesty, and help sweep away the rude idea of sex-secrecy”.

Retouched photographs, on the other hand, were “more likely to create squeamishness, hypocrisy, and misunderstanding, and thus retard the progress we are trying to make towards freedom and sanity”. Retouched bodies were described as “mutilated”, yet nudists acknowledged that the alternative, “a pictorial world where everyone turns his or her back to the spectator”, risked monotony.

Early nudist magazines in Britain met constraints about what they could picture even when they didn’t agree with the law’s assessment of what was obscene. The 1857 Obscene Publications Act had been established to prosecute pornographic works – but as both obscenity and pornography depended on the eye of the beholder, for over a century fresh debate was required in each case.

Lord Chief Justice Cockburn’s 1868 definition of obscenity endured for much of the 20th century: that which could “deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands a publication of this sort may fall”.

Given its vague premise, obscenity prosecution rested on a range of factors including “circumstances of publication”. Alec Craig, an ardent nudist and vociferous anti-censorship campaigner, advised in the 1930s that “snaps taken in a nudist camp cannot be considered ‘obscene’”.

This story is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism and is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects to tackle societal and scientific challenges.

But he warned: “What may be perfectly innocuous in one set of circumstances may be ‘obscene’ in another. To take an extreme example,” he noted, “nude photographs, quite unobjectionable in normal circumstances, might be held to be ‘obscene’ if circulated in a convent school.” Likewise, outside of the careful framing of the nudist magazine, a nude photograph carried a range of meanings that could prove hard to pin down in a court of law.

Nudist magazines published photographs to show the movement’s ideals but many members did not wish to be depicted for reasons of respectability. Few practitioners were professional photographers. Those who were preferred to use models as subjects.

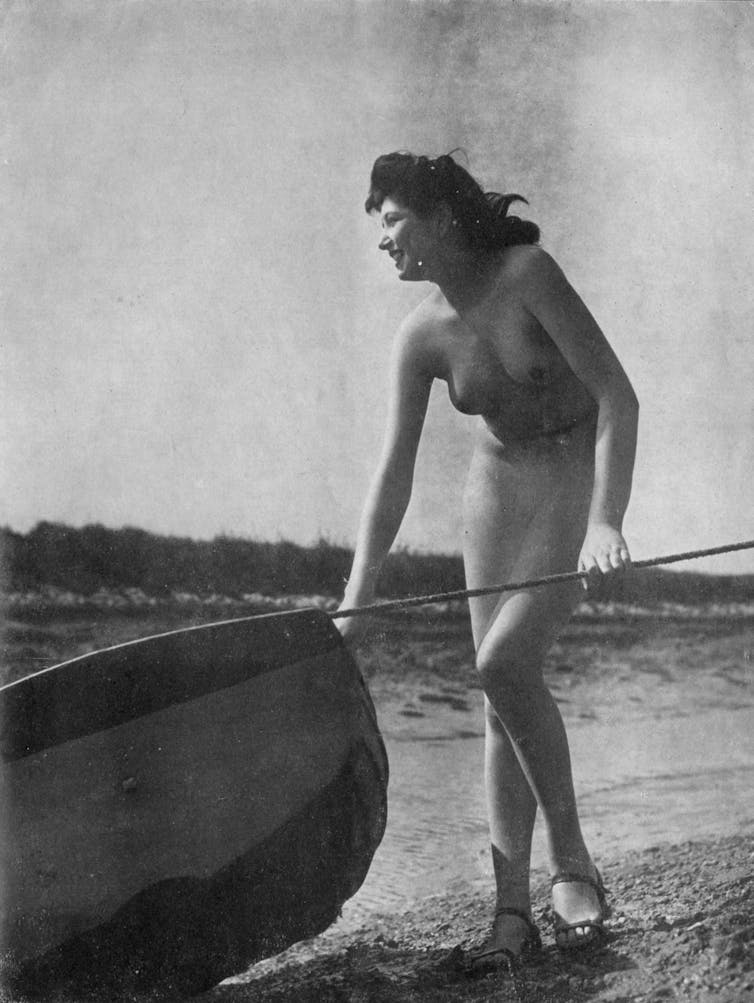

The emerging imagery of nudism was a mixture of candid photographs of camp life, painterly depictions of young slim bodies in pastoral settings, and action photographs showing athletic bodies exercising. As men’s bodies needed to be doctored with a heavier hand to pass the censor, and as nudism was dominated at the outset by men (as members, photographers, writers, editors and readers), nude women were its central photographic focus.

By the 1930s, female photographic nudes could be found on the walls of photography exhibitions as well as in the pages of art, anatomy and anthropology books, men’s magazines, daily newspapers, photojournalist weeklies and naturist monthlies. In some cases, with adjusted context, the same images could appear in all these locations, challenging nudism’s claims that its publications and its photographs were morally and aesthetically distinct.

The nude photograph on trial

This was the case with photographs by Horace Narbeth, professionally known as “Roye”, whose prolific and commercially adaptable imagery was repurposed for a wide range of audiences and arguments. Roye’s photographs, always of young women, often posed in outdoor settings, simultaneously articulated abstract notions of “beauty” and “womanhood” in art books, and ideas about “freedom” and “nature” in nudist publications. They illustrated technical guidance in photography magazines and offered titillation in pin-up pamphlets.

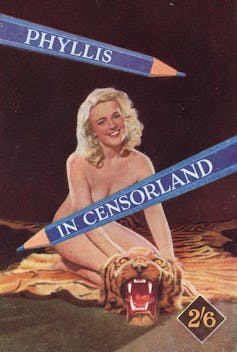

Roye had long been frustrated with British obscenity regulations and made play with what he perceived to be their hypocrisies in his 1942 publication, Phyllis in Censorland. The cover design showed burlesque dancer Phyllis Dixey, the so-called British queen of striptease, naked on a tiger skin rug, but with her breasts and genitals concealed by the blue pencils of the censor. Its contents comprised nude and near-nude photographs, accompanied by mocking verses. Each poem pilloried those who sought to protect public morals while enjoying privileged pleasures of surveillance.

Roye reissued his book during the mid-1950s when the seizure of printed material on obscenity grounds was at a new high. The 1951 Conservative government oversaw escalating destruction orders and extended punishments in a period when cheap magazines were booming. The desire to contain them led to a protracted legal power struggle.

In 1954, for example, around 167,000 books and magazines were seized, and imprisonments ranged from three to 18 months. In their enthusiasm to uphold public morals, magistrates ordered the destruction of eminent artistic and literary works including Boccaccio’s 14th century the Decameron.

In 1958, Roye went one step further and launched a private subscription series of un-retouched nudes under the title Unique Editions. Repurposing earlier negatives, including those previously included as retouched illustrations in nudist magazines, the buff-covered volumes each comprised photographs of nude female models with visible pubic hair, carefully interleaved between tissue pages that conferred both art value and a sense of revelation.

While the content included naturist-style nudes in rural environments, which could offer some legal protection, the photographs attracted police attention. A thousand copies were seized from Roye’s studio. He was called to court.

Before the jury, Roye positioned himself in the aesthetic avant-garde. Retouching, he argued, was a sacrifice of “artistic integrity”. His defence lawyer argued that:

Standards had changed since 1868, when pictures of Venus, in the Dulwich Gallery, had shocked Londoners; and it would be unrealistic to say that, in 1958, a photograph of a woman without clothing was an obscene thing.

Roye built a case that drew on both his gentlemanly standing and his professional photographer status. He compiled letters of support arguing for the public benefit of viewing nude photographs. His supporters shared arguments with nudists who believed that sex crimes would be eliminated and Victorian prudishness overturned.

In Roye’s case, however, the public need for openness and bodily display seemed only to apply to the viewing of young female models’ flesh. Nonetheless, he was acquitted.

Roye’s prosecution coincided with proposals to revise the Obscene Publications Act. Following public derision when acclaimed cultural works had been seized, 1959 amendments exempted from prosecution material with literary or artistic merit.

The nude was singled out for mention in parliamentary discussions about the problem of definition. The home secretary, Rab Butler, noted that nudes could be used for art historical lectures “to provide inspiration for the painter or photographer or, on the other hand, be degraded for the purposes of the pornographer’s wares”. Although MPs argued that it was “easy to tell the difference between the Song of Solomon and a collection of salacious photographs”, the problem was the evaluation of material in between.

Freedom of vision

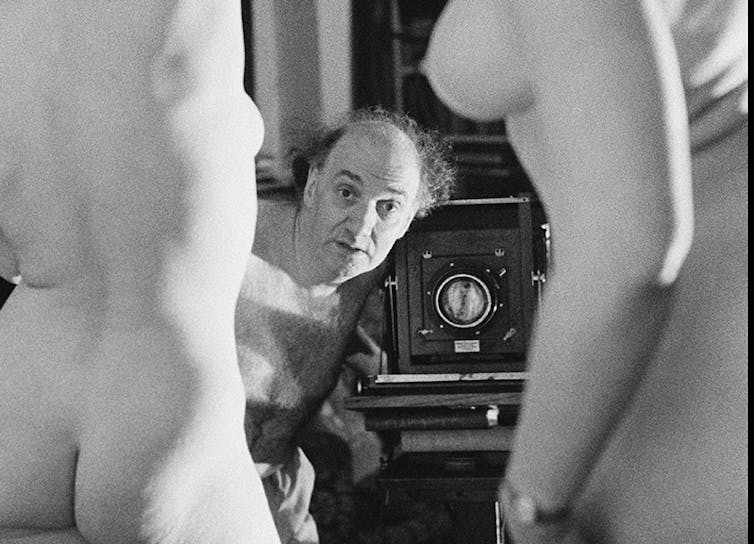

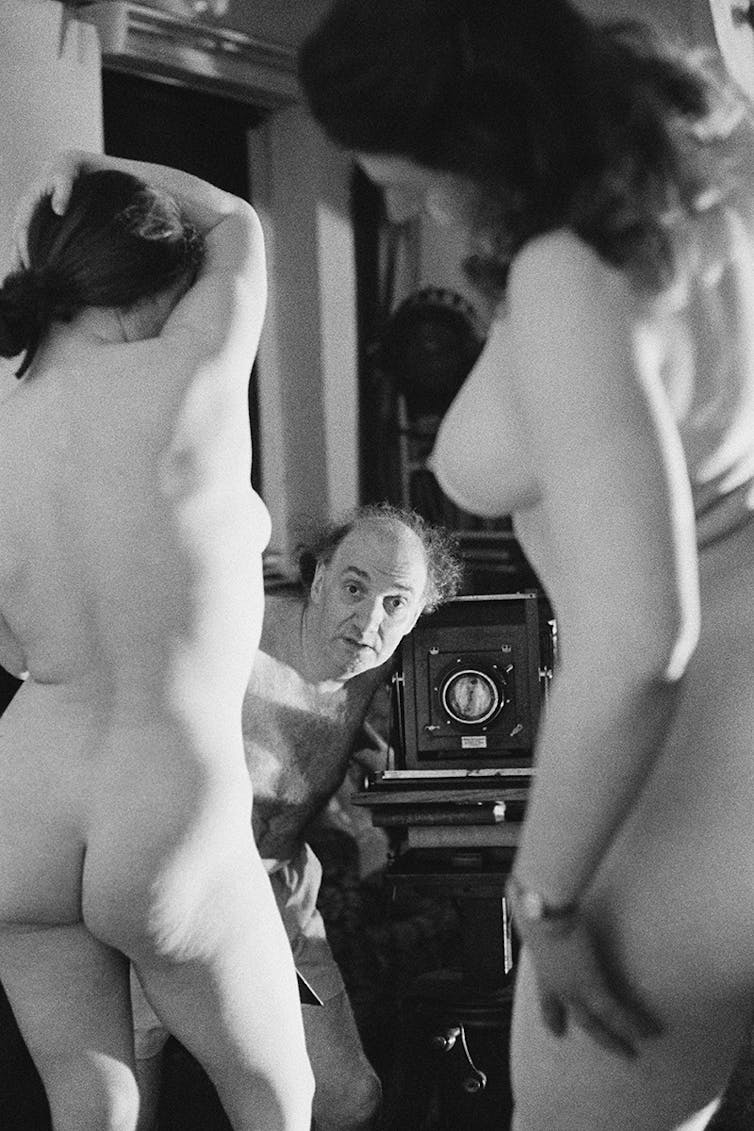

Not all nude photographers had such success in court. Ethelred Jean Straker was a Bohemian Soho photographer who ran a busy studio throughout the 1950s and 1960s providing classes for amateurs – mostly male – in the production of “artistic figure studies”, or nude photographs of models – always women. Straker tested the revised obscenity laws, but unlike Roye, he received guilty verdicts.

In 1958, he produced a book of nude photographs featuring pastiches of classical paintings alongside experimental lighting treatments in eclectic settings. It depicted female models amid looming shadows, dustbin lids, cellophane and vegetables.

Published in three languages, Straker’s book secured positive reviews from artistic luminaries but showed only a small, sanitised selection of his nude output, which extended to some 10,000 examples and included close-ups of women’s breasts, buttocks and genitalia.

The full range of Straker’s work could be viewed and ordered for purchase via his Femina gallery, above his Soho studio. In his advertisements for his services, Straker described the female nude rapturously as “a microcosm of the forces which play upon the mind and emotions of the creative person”. He claimed his studies offered “not only a sense of affective perception but also a source of unimpaired anatomical evidence”.

Despite Straker’s artistic, psychological and clinical framing, his nudes repeatedly drew the attention of the police. In 1961 police raided his premises, and seized nearly 2,000 display cards and negatives, of which the majority were deemed obscene.

In 1962, in the High Court, Straker was a thorn in the side of the prosecution. Highly informed about the 1959 Obscene Publications Act, Straker reminded the court of their obligation to “uphold and license the freedoms of expression of the artist”.

Using his trial as a soapbox, he declared that it was “no longer in the power of any magistrate to use a relegated heritage of authoritarian orthodoxy to lay down rules as to how a photographic artist should portray female anatomy or arrange a woman’s limbs”. Despite pleas for the value of his work to art and science, Straker lost the case and was fined £150 (about £5,000 at today’s value).

Undeterred, he continued to sell “unretouched” nudes by mail order until he was prosecuted again in 1965. By this time, Straker was aware of wider shifts in public attitudes to nude bodies, especially among the new generation, and he became a vocal anti-censorship campaigner, calling for “freedom of vision” alongside freedom of speech.

In 1967, he made headlines as Oxford University’s student magazine, Oxymoron, published one of his un-retouched female nudes. Entitled “Sun Worship”, the subject was a stylised studio portrait of a sun bather applying sun lotion under the shadow of a tree. The print had been among material previously seized in a police raid but a decade later it was published with university authorisation and escaped prosecution, illustrating the changing times.

By the end of the 1960s, the battle to show more flesh was complete. Largely fought by male photographers over the bodies of women, the so-called “pink wars” had been won. Un-retouched photographic nudes were openly published in pornographic magazines, naturist periodicals and art books alike.

New nude censorship debates

Whether this led to greater bodily liberation, especially for the young women who are most likely to be depicted, was a question raised by feminists at the time, and it remains open for debate. Even after permissive barriers were broken and greater bodily visibility was enabled, the trajectory of nude depiction has not been straightforward. Campaigns for visibility continue to arise in the present day with new agendas in nude representation.

Free the Nipple, for example, stakes similar claims in its calls for freedom from censorship on social media. Like earlier protests against the photographic retouching of genitals, its campaigners see the characterisation of women’s bodies as sexual and offensive – when male toplessness is considered neutral – as illogical.

But unlike earlier campaigners against retouching, it is now mostly young women leading the charge, creating the philosophies, taking the photographs and controlling consent.

Why has the showing of nudity remained so fraught? The issue remains one of context and intention. Naturists have argued hard that social nudity can be non-sexual, and naturism has fiercely protected legal status.

Photographs of nude bodies, however, naturist or otherwise, can serve a range of purposes and, like all photographs, they are open to a wide range of readings and meanings, reinterpretations and reuse. Photographers and publishers may argue for the value of full-frontal nudes to communicate health, artistry and freedom, but even photographs produced for non-sexual communication can serve sexual ends.

On social media, where photographic quantities are vast and mostly surveyed by machine, it is easier for Facebook to apply blanket bans than engage with individual nude images’ complexities. While it states that its policies have become more nuanced over time, they are still unable to cope with the sometimes subtle borderlines between categories. Facebook recognises that nudes can be used “as a form of protest, to raise awareness about a cause or for educational or medical reasons”, and says they make allowances “where such intent is clear”.

However, many forms of bodily display, including in artistic practice, do not fit Facebook’s frames, and intention is notoriously hard to gauge in a photograph. These were the technical and semantic distinctions on which nude photographers’ court cases were won and lost historically, and issues of intent and use remain today.

At the end of the second world war, nudist Michael Rutherford addressed “historians of the future” in his field guide, entitled British Naturism. He predicted that scholars would consider the practice “among the significant and important happenings of this, the 20th century”. He wrote: “If our grandchildren can say of us, as they grow up to a sane acceptance of their own bodies: ‘What was all that fuss about …?’ we shall have done our part.”

But a century after the founding of nudism as a social movement, and 50 years since non-manipulated nude photographs could be printed without fear of prosecution, the current censorship of nudes on social media seems regressive.

We are Rutherford’s grandchildren, but we certainly do not have the “sane” attitudes to nudity that he predicted.

Editor’s note: This article was amended on December 4. Peter Paul Rubens had been erroneously described as a 15th rather than 17th century artist.

For you: more from our Insights series:

- WitchTok: the rise of the occult on social media has eerie parallels with the 16th century

- The Prestige: the real-life warring Victorian magicians who inspired the film

- ‘We have nothing left’ – the catastrophic consequences of criminalising livelihoods in west Africa

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Annebella Pollen, Reader in the History of Art and Design, University of Brighton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.