By Fighting the Ozone Hole, We Accidentally Saved Ourselves

With the Montreal Protocol, life on Earth dodged a bullet we didn’t even know was headed our way.

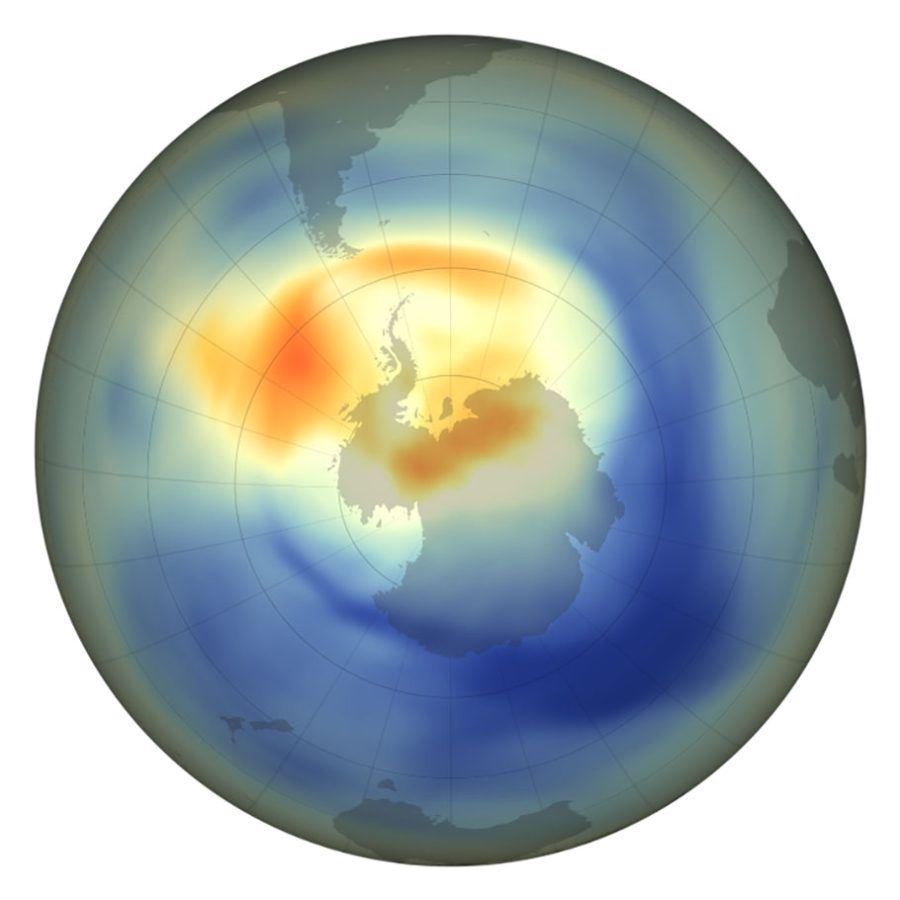

In 1985, the British Antarctic Survey alerted the world that in the atmosphere high above the South Pole a giant hole was forming in the Earth’s protective ozone layer. World leaders swiftly assembled to work out a solution. Two years later, the United Nations agreed to ban the chemicals responsible for eroding the layer of the stratosphere that shields Earth from the sun’s ultraviolet radiation. Known as the Montreal Protocol agreement, it is still one of the UN’s most widely ratified treaties.

The Montreal Protocol was a win for diplomacy and the stratosphere. But unbeknown to its signatories at the time, the agreement was also an unexpected ward against climate catastrophe. As new research shows, the aptly named ozone-depleting substances (ODSs) that created the hole over Antarctica are also responsible for causing 30 percent of the temperature increase we saw globally from 1955 to 2005.

Michael Sigmond, a climate scientist at Environment and Climate Change Canada is the lead author of a new study calculating the greenhouse-trapping potency of ODSs. The substances’ contribution to global warming are, he says, “larger than most people have realized.”

The Montreal Protocol regulates nearly 100 ozone-eating chemicals. Many fall under the umbrella of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), chemicals popularized in the 1930s for use in spray cans, plastic foams, and refrigeration. Compared with the array of toxic, flammable alternatives they replaced, CFCs were seen as wonder chemicals, and by the early 1970s, the world was producing nearly one million tonnes of them each year.

CFCs are inert, so they don’t react with other gases. Instead, they tend to accumulate in the atmosphere and drift wherever the wind takes them, hanging around in the air for 85 years or more. Once they reach the stratosphere, the second layer of Earth’s multilayered atmosphere, CFCs begin to break down. They’re “destroyed by being blasted apart by photons,” explains Dennis Hartmann, a climate scientist at the University of Washington who was not involved in the research. That reactive ruckus is what causes the hole in the ozone layer.

In the troposphere—the lowest level of the atmosphere, which fewer photons reach—ODSs act as long-lasting greenhouse gases. Back in 1987, scientists knew ODSs trapped some solar radiation, but they didn’t know how much. Only recently have scientists been putting together the evidence that ODSs are actually one of the most damaging warming agents of the past half century.

The effects of this warming are amplified at the poles. Sigmond and his colleagues’ work shows that if ODSs had never been mass produced—if the concentration in the atmosphere had stayed at 1955 levels—the Arctic today would be at least 55 percent cooler, and there’d be 45 percent more sea ice each September.

ODS production leveled off in the 1990s. But because they’re so long-lived, these gases are still kicking around, and the warming they cause is still increasing. Yet it could have been much worse. By banning ODSs, the Montreal Protocol unintentionally prevented 1 °C of warming by 2050.

With the Montreal Protocol, world leaders rallied around an urgent cause. In the process, we inadvertently phased out the second-largest forcer of global warming. The unanticipated benefits for the global climate, says Susann Tegtmeier, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Saskatchewan who was not involved in the study, “can be considered a very welcome and very positive side effect.”

While it’s taken a lot more negotiation and innovation to begin dislodging the main driver of climate change—carbon dioxide—the Montreal Protocol proves the power of collective action and shows how tackling environmental woes can help us in ways we didn’t expect.

Author: J. Besl is a writer in Anchorage, Alaska, where he writes about environmental change and contributes research stories for local universities. He has a master’s degree in water security from the University of Saskatchewan.

Credits: This article by J. Besl, https://hakaimagazine.com, is published here as part of the global journalism collaboration Covering Climate Now