The Politics of Religion in Asia: Balancing Pluralism and Identity

In the dense tapestry of Asia’s socio-political life, religion weaves a dominant thread, influencing not merely personal convictions but shaping the very ethos of national identities and legislative frameworks. The continent, a mosaic of beliefs ranging from the polytheistic spectacles of Hinduism to the monotheistic tenets of Islam and Christianity, and the philosophic subtleties of Buddhism and other indigenous faiths, serves as a fertile ground for an inquiry into the delicate balancing act between pluralism and religious identity. This investigation delves into how states grapple with the Herculean task of fostering harmony in diversity while safeguarding religious identities that are often inextricably linked to political narratives.

Asia’s religious landscape is a testament to historical confluences and the triumphs and tribulations of its civilisations. In India, Hinduism’s plurality, with its myriad deities and philosophies, coexists with Islam, Christianity, Sikhism, Buddhism, and a plethora of tribal faiths. The country’s constitution, a monumental document of legal scholarship, enshrines secularism and attempts to uphold the liberty of belief while simultaneously navigating the treacherous waters of majoritarian politics. The Indian narrative, however, is marred by periodic communal unrest and the politicisation of religion, where electoral gains are often secured by pandering to religious sentiments—a game of chess where the pawns are the very believers themselves.

Contrastingly, in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, religion forms the cornerstone of national identity. The state’s foundation lies in the desire for a Muslim homeland, yet it struggles with sectarian divides and the marginalisation of minorities. Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, ostensibly designed to protect religious sentiments, have drawn international concern for their potential misuse against dissenting voices and minorities, underscoring the ongoing tension between religious orthodoxy and human rights.

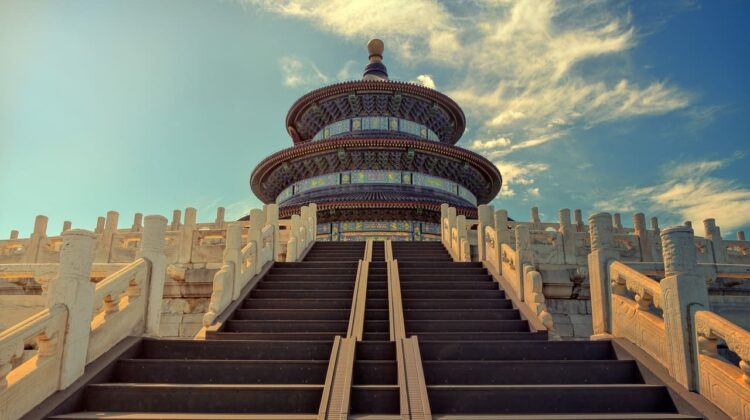

Moving eastward, the People’s Republic of China presents a unique case where religion is tightly regulated under the aegis of a secular, yet authoritarian regime. Here, the state’s emphasis on control is evident in its uneasy relationship with Tibetan Buddhism and the Muslim Uighurs of Xinjiang. The Chinese model raises probing questions about the price of religious identity in the face of national unity and security.

In the archipelago of Indonesia, the largest Muslim-majority country in the world, Pancasila—the state ideology—espouses religious tolerance and pluralism. Despite this, Indonesia has witnessed the rise of conservative Islamic groups that challenge this inclusive vision, reflecting a global trend towards religious conservatism and its implications for pluralistic societies.

The Asia-Pacific region also confronts the quandaries of religious nationalism and its implications for democracy and civil liberties. In Myanmar, the plight of the Rohingya Muslims is a stark illustration of how religious and ethnic identities can be weaponised to justify exclusion and violence, raising pressing ethical questions about the international community’s responsibility to protect.

The intricate interplay of religion and politics in Asia is not a mere academic discourse but resonates with the lived realities of billions. Statesmanship in Asia, thus, necessitates not only a judicious approach to religious sensitivities but also a visionary leadership that can transcend the allure of populism and weave a narrative of inclusivity.

The quest for balance is fraught with challenges as it demands a recalibration of policies and perspectives in the face of changing global dynamics, such as the rise of religious extremism, the proliferation of social media, and the rekindling of regional hegemonies. How Asian countries navigate these waters will not only shape their domestic peace and progress but will also have profound implications for global geopolitics and the collective quest for a harmonious world order.

Thus, ‘The Politics of Religion in Asia: Balancing Pluralism and Identity’ is not merely a reflection on the current state of affairs but a clarion call to policymakers, religious leaders, and civil society to engage in a nuanced dialogue that fosters mutual respect and coexistence. It is an invitation to acknowledge the complex historical legacies, socio-political intricacies, and the aspirational ethos of pluralism that could pave the way for a peaceful and prosperous Asia.

This exploration, while extensive, merely scratches the surface of a vast and multifaceted discourse. It is a call to look beyond the prism of preconceived notions and to embrace the diversity that has been the hallmark of Asian civilisation since time immemorial. The politics of religion in Asia, therefore, is a dance of shadows and light, where the nuances often hold the key to understanding the broader picture.

Continuing with the thread of our exploration, it becomes evident that Asia’s political leaders often walk a tightrope, balancing the imperative of social harmony against the potent force of religious identity. This balancing act is not merely a matter of domestic policy but resonates on the international stage, where perceptions of religious freedom and state-sponsored religion often collide with geopolitical interests and global human rights standards.

The Southeast Asian city-state of Singapore exemplifies a proactive approach to managing religious diversity through stringent laws and policies promoting multiculturalism. The Maintenance of Religious Harmony Act is one such legislative tool, crafted to prevent religious entities from meddling in politics and sowing discord. Singapore’s model, while not perfect, showcases the potential for legislative frameworks to mediate the complex relationship between religion and politics.

In the context of the Philippines, predominantly Catholic, yet with a significant Muslim minority in the southern region of Mindanao, the historical peace process underscores the interplay of religious identity with issues of autonomy and governance. The Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao stands as a testament to the intricate negotiations required to intertwine religious identity with political autonomy, albeit amidst ongoing challenges of implementation and the spectre of radicalisation.

In the Himalayan expanse of Nepal, once the world’s only Hindu kingdom, the transition to a secular state has been a seismic shift in its constitutional ethos. Yet, the undercurrents of Hindu nationalism remain a formidable influence, affecting everything from social policy to diplomatic relations. The transition, still unfolding, offers insights into the complexities of redefining national identity in a deeply religious society.

Japan, with its syncretic blend of Shinto and Buddhism, offers a contrasting narrative where religion subtly infuses national identity without the overt political entanglements seen elsewhere in Asia. Here, religious traditions underpin cultural identity and national ceremonies, yet the constitutional commitment to secular governance remains unchallenged. It is a nuanced example of how religion can inform national consciousness without dictating political agendas.

The Korean Peninsula presents another facet of this complex picture. In South Korea, Christianity has seen a remarkable growth, influencing everything from social movements to foreign policy. In stark contrast, North Korea maintains a stringent state-imposed atheism, with the regime itself taking on a quasi-religious mantle—an extreme example of the state’s control over religious expression.

In light of these varied landscapes, it becomes clear that religion in Asia cannot be neatly compartmentalised or isolated from the socio-political fabric of its diverse nations. The challenge for Asian states is to craft policies that are not only responsive to the spiritual needs of their populations but also to the imperatives of social cohesion and the demands of an increasingly interconnected world.

The interplay between religion and politics in Asia is a dynamic and evolving narrative, influenced by internal pressures and external forces. As Asian economies continue to grow and their geopolitical influence expands, the world’s focus on how these nations manage the politics of religion will intensify. The outcomes will have far-reaching consequences, not just for the citizens of these countries but for the broader patterns of global interaction.

In conclusion, ‘The Politics of Religion in Asia: Balancing Pluralism and Identity’ is a narrative that is continuously being written. It is a story of contrasts and contradictions, of harmony and conflict, and of the ongoing search for a middle path that respects religious convictions while forging a common identity. The discourse is complex, but it is crucial for understanding the future of a region that is home to some of the world’s oldest civilizations and some of its most pressing contemporary challenges. The way forward lies in dialogue, understanding, and an unwavering commitment to the universal values of dignity, respect, and mutual coexistence.

Author: Donglu Shih

Expert in Asian culture and economics. She collaborates with major companies in the field of international relations. Collaborates with The Deeping on Asian political topics