Sen. Mitch McConnell’s legacy is the current Supreme Court and a judiciary reshaped by his ‘calculated audacity’

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell departs the Senate chamber on February 28, 2024 in Washington, DC. Photo by Nathan Howard/Getty Images

Al Cross, University of Kentucky

Mitch McConnell, who announced on Feb. 28, 2024, that he would step down as the Senate GOP leader later in the year, used his tenure as the longest-serving Senate leader of any party to remake the federal judiciary from top to bottom.

His success could hardly have been predicted when Senate Republicans elected McConnell as their leader in 2006. For most of the 40-plus years I have watched McConnell, first as a reporter covering Kentucky politics and now as a journalism professor focused on rural issues, he seemed to have no great ambition or goals, other than gaining power and keeping it.

He always cared about the courts, though. In 1987, after Democrats defeated Supreme Court nominee Robert Bork, McConnell warned that if a Democratic president “sends up somebody we don’t like” to a Republican-controlled Senate, the GOP would follow suit. He fulfilled that threat in 2016, refusing to confirm Merrick Garland, Barack Obama’s pick for the Supreme Court.

Keeping that vacancy open helped elect Donald Trump. Two people could hardly be more different, but the taciturn McConnell and the voluble Trump have at least one thing in common: They want power.

Trump had exercised his power with what often seems like reckless audacity, but McConnell’s 36-year Senate tenure is built on his calculated audacity.

McConnell’s political rise

It was audacious, back in 1977, to think that a wonky lawyer who had been disqualified from his only previous campaign for public office could defeat a popular two-term county executive in Louisville.

McConnell ran anyway.

It was audacious to think that a Republican could get the local labor council to endorse him in that race, but he got it, by leading the members to believe he would help them get collective bargaining for public employees.

McConnell won the race. He didn’t pursue collective bargaining.

Seven years later, it was audacious to think that an urbanite who wore loafers to dusty, gravelly county fairs and lacked a compelling personality could unseat a popular two-term Kentucky senator, especially when he trailed by 40 points in August. But McConnell won.

As soon as he won a second term in 1990, McConnell started trying to climb the Senate leadership ladder, facilitated in large measure by his willingness to be the point man on campaign finance issues, an area his colleagues feared. They reacted emotionally to this touchy issue; he studied it, owned it and moved higher in the leadership.

Business, not service

In politics, lack of emotion is usually a drawback. McConnell makes up for that by having command of the rules and the facts and a methodical attitude.

The recording on his home phone once said, “This is Mitch McConnell. You’ve reached my home. If this call is about business, please call my office.”

Business. Not something like “my service to you in the United States Senate,” but “business.”

This lack of emotion keeps McConnell disciplined. I am not the only person he has told, “The most important word in the English language is ‘focus,’ because if you don’t focus, you don’t get anything done.”

Five years ago, I spoke to the McConnell Scholars, the political-leadership program he started at the University of Louisville. One thank-you gift was a letter opener bearing two words: focus and humility. The first word was no surprise, because of McConnell’s well-known maxim; the second one intrigued me.

The director of the program, Gary Gregg, says adding “humility” was his idea. But it fits the founder. With his studied approach and careful reticence, McConnell is the opposite of bombast, and that surely helped him gain the Republican leader’s job and stay there. He has occasionally described his colleagues as prima donnas who look in the mirror and see a president, something he claims to have never done.

When the colleagues in your party caucus know you are focused on their interests and not your own, you can keep getting reelected leader, as McConnell has done without opposition every two years since 2006.

McConnell’s Supreme Court

McConnell’s caucus trusts him. When he saw Obama as an existential threat – someone who could bring back enough moderate Democrats to give the party a long-term governing majority – McConnell held the caucus together in opposition to Obamacare, and Republicans used that as an issue to rouse their base in the 2010 midterm election.

Meanwhile, McConnell was working on the federal judiciary. He and his colleagues slow-walked and filibustered Obama’s nominees, requiring “aye” votes from 60 of the 100 senators to confirm each one. The process consumed so much time that then-Majority Leader Harry Reid abolished the filibuster for nominations, except those to the Supreme Court.

That sped up the process, allowing Obama to appoint 323 judges, about as many as George W. Bush. But Republicans’ additional delaying tactics still left 105 vacancies for Trump to fill.

When Democrats weakened the filibuster, McConnell warned, “You’ll regret this. And you may regret it a lot sooner than you think.”

Democrats may now concede that point. McConnell and Trump put nearly 200 judges on the federal courts, making them all the more a white-male bastion of judicial conservatism.

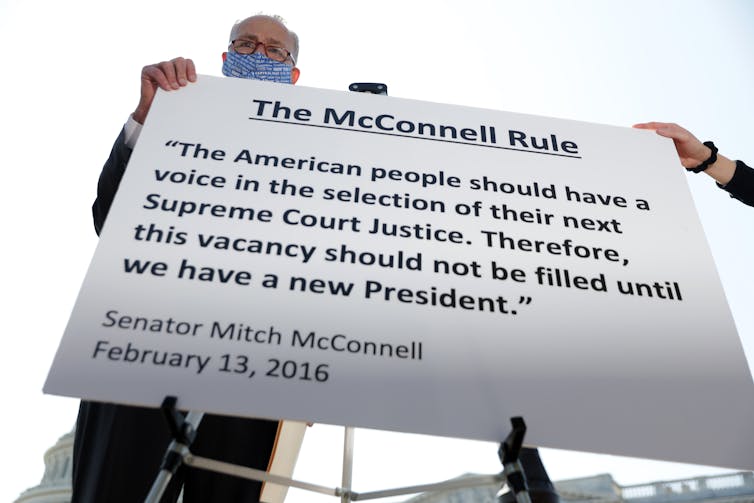

When Justice Antonin Scalia died in February 2016 and McConnell said the seat wouldn’t be filled until after the November election, it was another case of calculated audacity.

Democrats cried foul, but they were powerless to reverse his decision because Republicans stuck with him.

Trump’s 2016 victory preserved the Senate Republican majority, which then did away with the Supreme Court exception, allowing McConnell and his colleagues to install by simple majority vote the sort of Supreme Court justices they wanted: Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett.

It is the Roberts Court, but it is also the McConnell Court.

This is an updated version of an article originally published Oct. 1, 2020.

Al Cross, Professor and director emeritus, Institute for Rural Journalism, University of Kentucky

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.