Ukraine war: capture of key Black Sea outposts and strike on Crimea show Kyiv’s increasing confidence

Gavin E L Hall, University of Strathclyde

The recapture, by Ukrainian forces, of the oil and gas platforms off the coast of Crimea known as the “Boyko towers” has both strategic and symbolic significance. Their position, between the westerly-most point of Crimea and Snake Island, in waters close to Ukraine’s border with Romania, puts them in a key location for monitoring Russian activities in the Black Sea.

Russia had seized control of these drilling platforms in 2015, in the wake of its annexation of Crimea the previous year. It used them for military purposes including installing radar equipment that gave them surveillance of the sea between Ukraine and the Crimean peninsula.

Announcing the recapture of the platforms, which reportedly took place at the end of August, Ukraine’s intelligence service, the GUR, stated that: “Russia has been deprived of the ability to fully control the waters of the Black Sea, and this makes Ukraine many steps closer to regaining Crimea.”

Though the Bokyo towers are oil and gas platforms, they contain helipads and have the potential to host missile systems. They also provide underwater and surface reconnaissance and monitoring. Control of the platforms greatly enhances Ukraine’s ability to operate in the Black Sea, while at the same time reducing Russian capabilities.

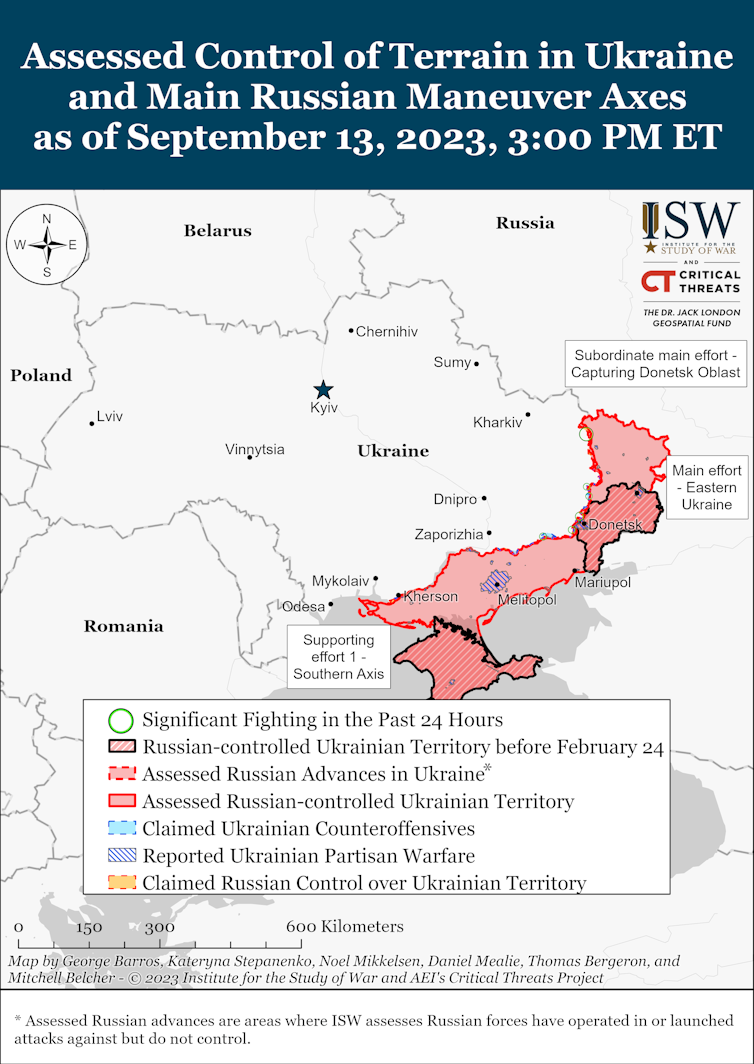

Ukraine’s ground counteroffensive continues to pressurise Russian defences in the east and south. But in recent months, Kyiv has also directed airborne attacks on targets inside Russia, including drone attacks on Moscow itself. And a missile strike on Russia’s naval installation in Sevastopol – Ukraine’s biggest attack on Russian facilities in annexed Crimea so far – highlights Kyiv’s growing missile capabilities.

That attack, reported to have involved ten western-supplied cruise missiles and three unmanned boats, targeted a dry dock servicing Russia’s Black Sea fleet. Ukrainian sources claimed a Ropucha-class landing ship and a Kilo-class submarine were both directly hit and set ablaze.

Russian weakness

Regaining control of the Boyko towers and the strike on Sevastopol are notable morale-boosters at a crucial phase of Ukraine’s wider offensive operations.

The success of Kyiv’s spring and summer counteroffensive has been a source of fierce debate. A great deal of attention has focused on what is seen by many as the relatively slow progress made by Ukrainian forces, faced with Russia’s considerably strengthened defensive lines. This is lending weight to those who are arguing for a negotiated ceasefire in the face of the massive cost of supplying arms to Ukraine.

After spending the winter and much of the early part of the year in an attritional battle for the town of Bakhmut, in which both sides lost thousands of men for insignificant territorial gains, the majority of Russia’s offensive operations have been limited to missile and drone strikes. Kyiv announced recently that Russian strikes had targeted 105 port facilities, severely restricting the country’s ability to export grain.

Russia’s bombardment has also aimed to erode the Ukrainian people’s will to fight. Yet it’s Russian morale – both military and domestic – which remains under question, thanks to a shortage of ammunition and depleted reserves of troops. The Kremlin is reported to be debating a second wave of mobilisation in October and November. The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) has reported a Russian Telegram channel which claims the Kremlin wants to mobilise at least 170,000 reservists and recruit a further 130,000 contract military. The post, quoting intelligence sources, says that the plan is to “replenish the ranks of the army … within a short time window – before the start of the active presidential campaign in 2024”.

Meanwhile, Vladimir Putin hosted the North Korean president, Kim Jong-un, in Vladivostok on September 13. The pair reportedly discussed a deal whereby North Korea would supply Russia with ammunition, primarily artillery shells that Russia is using far more quickly than it can manufacture them. In return, Russia would provide expertise for North Korea’s satellite programme, which has hitherto been unsuccessful.

The overall image presented by these events is not one of Russian strength.

Ukraine battles on (slowly)

Despite this apparent Russian weakness, the slow progress of Ukraine’s counteroffensive is causing a degree of concern in the west. The large amount of sophisticated weaponry supplied by Kyiv’s allies – as well as training of Ukrainian officers in programmes such as Operation Interflex – has increased expectations of more rapid progress towards Ukraine’s goals.

The key goal at present involves breaking through Russia’s defensive lines in the south, with the aim of driving southwards towards the Sea of Azov and effectively cutting Russia’s land bridge to Crimea. Yet Ukraine has struggled to break through these lines apart from in isolated instances, such as around Robotyne in the western Zaporizhzhia Oblast. Ukrainian troops are reported to be making small daily advances in both Zaporizhzhia and further east around Bakhmut, where fierce fighting continues.

Ukraine‘s foreign minister, Dmytro Kuleba, reacted sharply at the end of August when he told a meeting of EU foreign ministers in Spain: “I would recommend all critics to shut up, come to Ukraine and try to liberate one square centimetre by themselves.” Nato’s secretary-general, Jens Stoltenberg, also sought to quieten western critics, telling CNN: “Ukrainians have exceeded expectations again and again … We need to trust them.”

But it’s clear that Kyiv’s allies in the west will be watching Ukraine’s progress in the field carefully over the next few weeks. They will be hoping for significant movement before the changing weather forces a slowdown in the field, and gives Russia the chance to regroup and rebuild its defensive fortification.

Gavin E L Hall, Teaching Fellow, Political Science and International Security, University of Strathclyde

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.