How El Niño and La Niña climate patterns form

by Clark Merrefield, The Journalist’s Resource

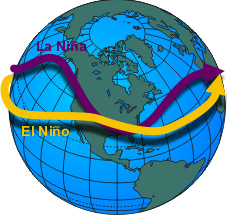

Trade winds usually push warm water across the Pacific westward toward Oceania and Asia, causing cold water to surface along the coastlines of the tropical Americas, including parts of Mexico, Central America and South America.

But every few years, trade winds weaken during the early spring, and warmer water settles around these coasts and into the mid-Pacific.

This phenomenon is part of a broader climate pattern called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation. The warm phase of ENSO is simply called El Niño. Stronger than usual trade winds, by contrast, push warm water westward, allowing more cool water to surface and bringing a La Niña pattern. El Niño and La Niña occur naturally, though recent research suggests climate change is affecting these patterns.

Fishermen in Peru first identified warmer than usual waters in the Pacific during the 1600s, and named the phenomenon “El Niño de Navidad,” since it often occurred near Christmas. Usually the rising, nutrient-rich cool waters brought a wealth of sea life to their nets. But once in a while, the bounty would shrink, coinciding with warmer waters the fishermen observed, typically during December.

Likewise, trade winds are naturally occurring and move east to west. For centuries, sailors used them to speed their cargo ships across oceans. Historical evidence suggests El Niño winds spurred the Spanish conquest of South America, allowing ships to reach northwestern parts of the continent that winds in years past had kept them from reaching. Climatologists are not entirely sure why trade winds weaken — sometimes they weaken seemingly randomly.

But Wenju Cai, director of southern hemisphere oceans research at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Australia, explained by email that “we know a bit.”

Cai pointed to the behavior of the Madden-Julien Oscillation, a moving mass of clouds, rain and wind over the Indian Ocean, discovered by climatologist Roland Madden and meteorologist Paul Julian in the 1970s, as one link to the intensity of trade winds over the Pacific.

El Niño patterns also mean shifting jet streams. Jet streams are currents of air that move roughly west to east and flow above trade winds. They are strongest around 6 to 8 miles above the earth’s surface, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Warmer Pacific waters cause the Pacific jet stream to dip south and extend across the southern U.S. and northern Mexico during strong El Niño years.

Jet streams form boundaries between warmer and cooler air, and high and low pressure. High pressure systems are more likely to bring fair weather and clearer skies, while low pressure systems are more likely to bring stormier weather.

During winter in the northern hemisphere, this dip in the jet stream typically results in warmer temperatures across much of Canada and the middle of the U.S., as well as more rain and flooding in southern California. Much of the Southeast, especially around the Florida panhandle, often gets cooler temperatures, as this area is just south of where the jet stream typically settles during El Niño.

This piece is a companion to our comprehensive explainer, “El Niño: What it is, how it devastates economies, and where it intersects with climate change.”

This article first appeared on The Journalist’s Resource and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.