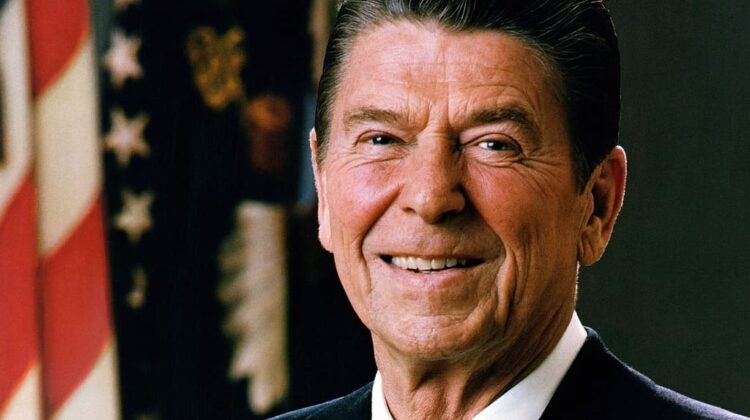

Forty years after Ronald Reagan was re-elected, Republicans want Reaganism back

James Cooper, York St John University

With everything else that is going on in US politics, it would be easy to forget the 40th anniversary of Ronald Reagan’s landslide re-election in 1984.

But Donald Trump and his supporters seem keen on keeping the memory of Reagan alive, and building on his foundations. Project 2025 – the 920-page blueprint for a second Trump term from conservative thinktank the Heritage Foundation – mentions Reagan 71 times. These references include those who worked for him and have also contributed to the report, and examples of how the think tank successfully influenced the Reagan administration.

The Heritage Foundation claims it had massive influence in the 1980s, with 60% of its policy recommendations introduced by Reagan, and hopes for the same under Trump with its “bold and courageous plan”.

Reagan was well known for his hands-off management style; Trump might also be happy for others to fill in the details to his pledge to “Make America Great Again”.

Comparisons have also been made during the 2024 campaign between “the Gipper” (Reagan) and Trump in terms of their leadership style and blurring of status between politician and celebrity.

Reagan’s landslide

So what is it about Reaganism Trump supporters want to redeploy? The 1984 election was a defining moment for the Republican party, with Reagan only the sixth Republican president to win successive elections. Trump borrows the slogan used by Reagan in 1980, wanting to “Make America Great Again”.

Between 1984 and 2016, the Republicans were the party of Reagan, with his supporters claiming that he had reversed US economic decline, restored national prestige, won the cold war and put the family at the heart of American politics. Reagan’s rhetoric of small government and lower taxation inspired his successors in the Oval Office – George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush – and Republicans in Congress. The Democrats were even forced to become “New Democrats” in response to Reaganism in order to get back into power.

Culture wars (again)

There are undoubtedly similarities between Reagan and Trump. For instance, their appeal to blue-collar voters, tax cutting policies, strong national defence, and what we would now describe as “culture war” rhetoric. Project 2025 evokes this history: “In 1979, the threats we faced were the Soviet Union, the socialism of 1970s liberals, and the predatory deviancy of cultural elites. Reagan defeated these beasts by ignoring their tentacles and striking instead at their hearts.”

Reagan and Trump both had established careers on screen before coming into politics. As the first president from an entertainment background, particularly his time in Hollywood, Reagan was a master of the camera and earned his title of “The Great Communicator”.

However, there are significant differences between the two leaders in both tone and policy. Reagan governed as a pragmatist and was civil towards his opponents – be they Democrat or Republican. His time as chair of the Screen Actors Guild (the actors’ union) helped him understand the art of the negotiation, but he used it against the unions as president. He became a tough deal maker as his settlement of the air traffic controllers strike showed. But unlike Trump, Reagan often brought optimism to his campaigns, clearly shaped by his midwestern childhood and his years in Hollywood.

Trump’s fame from reality television, and his business empire, meant that he was able to bypass traditional political pathways to the White House. He certainly knows how to use his screen time in front of the cameras and win over his audience. Yet Trump’s style can be more combative and polarising than Reagan’s.

Reaganism v Trumpism

Two areas of public policy underline the difference between Reagan and Trump. The former signed the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act, granting amnesty to around three million undocumented immigrants so that they could legally remain in what the president referred to as the “shining city on a hill”.

In contrast, from the moment he announced his campaign, Trump redefined the Republican party to one advocating deporting millions of immigrants. In cultural issues, Reagan was vocal in his support for prayer in public schools and opposition to abortion, but he never introduced any legislative change to either of these issues.

Trump is embraced by the religious right, and readily takes credit for his Supreme Court appointments, which led to the overturning of Roe v Wade in 2022, and has reduced access to abortion for many women in the US.

Remaking government

Trump’s previous term and ongoing conservative language prompted the Heritage Foundation to launch Project 2025. This document calls for a remaking of the federal government and US public policy along conservative principles, such as giving more power to the president, and radical reforms of the civil service and even the FBI.

Trump and his acolytes will look to repeat the dramatic changes in domestic policy achieved in Reagan’s first term. In his first year, Reagan introduced US$39 billion (£30 billion) in budget cuts into law, including reducing spending on social welfare, as well as a massive 25% tax cut. The administration strongly advocated free-market economics and cutting federal regulation.

With Trump’s first term limited by advice and constraints placed upon him by his staff, the separation of powers in the US constitution and perhaps the reluctance of some mainstream Republicans to join his administration, a potential second term could mean an emboldened Trump administration, ready to take a more radical approach.

Reagan changed the Republicans so much that his vice-president, George H.W. Bush, essentially won on the promise of a third term of Reaganism. The longevity of Trumpism may depend on whether the Grand Old Party, the nickname for the Republicans, really is now the Trump party.

James Cooper, Associate Professor of History and American Studies, York St John University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.