What Syria’s rebel takeover means for the region’s major players: Turkey, Iran and Russia

Natasha Lindstaedt, University of Essex

When I was buying coffee at a cafe owned by a Syrian man in the UK on Sunday, I asked him what he made of the news that longtime dictator Bashar al-Assad had been ousted from power. He responded optimistically that he and the 7 million Syrians that had fled throughout the country’s civil war were eager to return.

Assad and his family have reportedly fled to Russia, leaving Syrians free to roam through his presidential palace. They toppled statues of Hafez al-Assad, Bashar’s father, who also ruled the country with an iron fist.

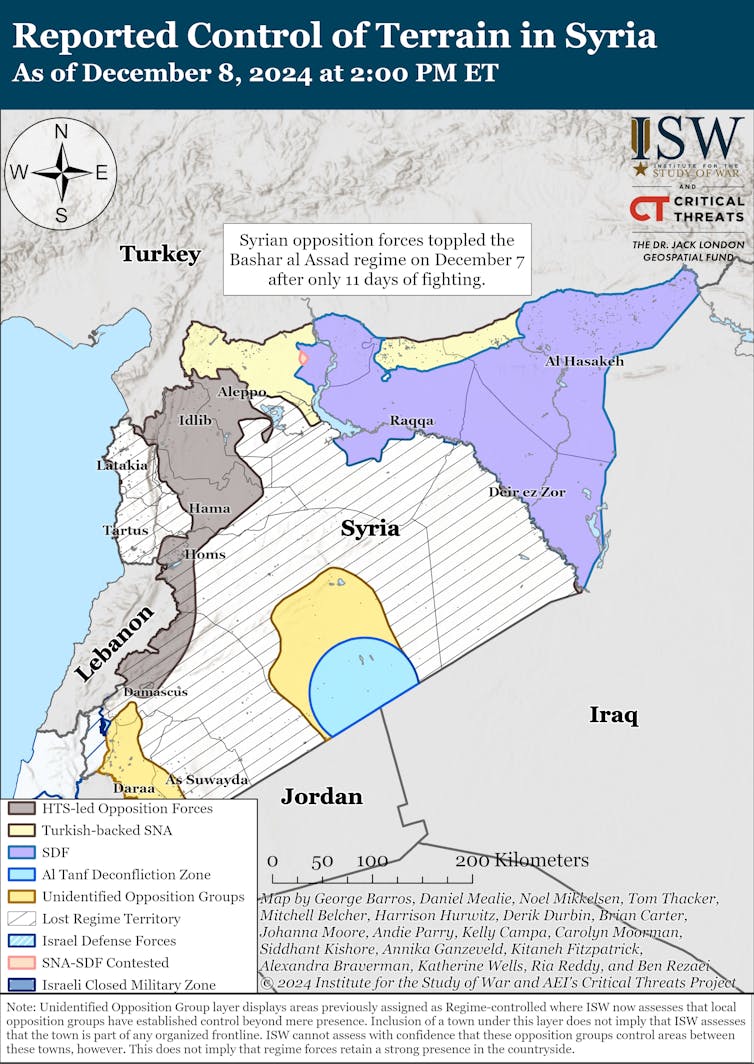

But Syria is now fragmented into regions controlled by disparate armed factions that have enjoyed backing of varying degrees from Russia, Iran, Turkey, the US, the Gulf states and Israel. There will be continued support for each of these armed factions by these major international powers, which will be vying to ensure their regional interests are preserved.

The most powerful rebel group is Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). From its power base in the north-western province of Idlib, HTS captured Aleppo in late November and then Hama, Homs and soon after the capital Damascus further south.

HTS had originally set up in 2011 as an affiliate of al-Qaeda, with Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi directly involved in its formation. Formerly known as Al Nusra, it eventually broke ranks with al-Qaeda in 2016 and merged with other militias to set up a new organisation under its current name.

The group was purged of its more extremist elements, even arresting al-Qaeda-linked individuals in the territory that it controlled. In an effort to Syrianise the organisation, HTS has not called for the founding of a global caliphate. It has instead focused on toppling Assad and expelling Iranian militias that it views as a threat to its own organisation which also increase the risk of Syrians mobilising along sectarian lines.

HTS took advantage of a 2020 ceasefire between Turkey and Russia to establish its organisational structure and build its governance efforts, with some support from Turkey in the form of arms and drones.

Regional implications

Turkey’s support for rebel groups such as HTS was critical to the recent offensive. Ankara gave the rebel organisations the green light to go ahead with their offensive after the Assad regime rebuffed its efforts to normalise relations with Turkey. Given the success of the offensive, Turkey will probably emerge as the most influential foreign actor in the country.

Having taken in more Syrian refugees than any other country, Turkey will be eager to allow Syrians to return home. But its main interest there is to topple the Kurdish forces in the north where the Democratic Union party (PYD), an offshoot of the banned Kurdistan Workers’ party (PKK), operates. Ankara will also want to ensure that any government that emerges in Syria is friendly to Turkey and not Iran.

For Iran, the ousting of Assad is a huge loss. It has now lost a land bridge to the eastern Mediterranean, an important base for Iranian proxies such as Hezbollah, and a route through which weapons could reach Lebanon. The loss of Iran’s strategic depth in Syria will weaken its ability to support Hezbollah at a time when it has been severely weakened by its conflict with Israel.

The loss is similarly huge for Russia. Moscow shored up Assad by sending thousands of Russian troops in 2015 and engaging in brutal airstrikes on Syrian rebel groups and civilian infrastructure. But Russia was too distracted and burdened by its war in Ukraine to maintain the level of support that Assad would have needed. As a result, Russia’s project in the Middle East ended in a spectacular failure.

There are now questions about the future for Russian military bases in Syria. Russia was granted a 49-year lease in 2015 on an air base and a naval base in Syria in order to gain a foothold in the eastern Mediterranean. These bases became critical hubs for the transfer of military contractors in and out of Africa where Russia has been tapping into anti-western sentiment to boost its influence.

But it is not clear what Syria’s new government will be willing to allow. Russian diplomats have been fleeing Damascus en masse and Russia may not have the capacity at the moment to deal with the fallout.

Rebuilding the Syrian state

As far as the future for Syria, international efforts to broker a lasting peace have been very unsuccessful. When Turkey, Iran and Russia tried to engineer peace talks in Kazakhstan in 2017, the result was political deadlock. The country was divided geographically between different factions.

Indeed, HTS is not the only powerful militia in Syria’s umbrella group of rebels. The Kurdish-led Syrian Defence Forces (SDF) currently control the northeast. They have also gained ground, taking advantage of the collapse of the Syrian army to capture the main desert city of Deir ez-Zor.

If they continue to enjoy US backing, the SDF will be determined to maintain these territorial advances. The outgoing US president, Joe Biden, has claimed to remain committed to providing this support, much to the annoyance of Turkey which views the SDF as a terrorist group.

There is also the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army, which brought together a number of armed groups in 2017 and took control of parts of northwestern Syria. The Syrian National Army is not cohesive or centralised and its various groups have often clashed with one another. But it remains a major player in Syria, and will aim to create a buffer zone near the Turkish border to prevent Kurdish militias from threatening Turkey.

Russia and Iran are no longer the major players in Syria. But if the rebel groups in Syria cannot build a transitional government of unity and stability, other actors will move in quickly to fill the void. It will be critical that Syrians – both those returning and those who never left – rebuild their new Syrian state on their own terms.

Natasha Lindstaedt, Professor in the Department of Government, University of Essex

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.